Following a challenge proposed by Gael to my

group I compared several implementations of

Logistic Regression. The task was to implement a Logistic Regression model

using standard optimization tools from scipy.optimize and compare

them against state of the art implementations such as

LIBLINEAR.

In this blog post I'll write down all the implementation details of this

model, in the hope that not only the conclusions but also the process would be

useful for future comparisons and benchmarks.

Function evaluation

The loss function for the $\ell_2$-regularized logistic regression, i.e. the

function to be minimized is

$$

\mathcal{L}(w, \lambda, X, y) = - \sum_{i=1}^n \log(\phi(y_i w^T X_i)) + \lambda w^T w

$$

where $\phi(t) = 1. / (1 + \exp(-t))$ is the logistic

function, $\lambda w^T w$ is

the regularization term and $X, y$ is the input data, with $X \in

\mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$ and $y \in \{-1, 1\}^n$. However, this formulation is

not great from a practical standpoint. Even for not unlikely values of $t$

such as $t = -100$, $\exp(100)$ will overflow, assigning the loss an

(erroneous) value of $+\infty$. For this reason , we evaluate

$\log(\phi(t))$ as

$$

\log(\phi(t)) =

\begin{cases}

- \log(1 + \exp(-t)) \text{ if } t > 0 \\

t - \log(1 + \exp(t)) \text{ if } t \leq 0\\

\end{cases}

$$

The gradient of the loss function is given by

$$

\nabla_w \mathcal{L} = \sum_{i=1}^n y_i X_i (\phi(y_i w^T X_i) - 1) + \lambda w

$$

Similarly, the logistic function $\phi$ used here can be computed in a more

stable way using the formula

$$

\phi(t) = \begin{cases}

1 / (1 + \exp(-t)) \text{ if } t > 0 \\

\exp(t) / (1 + \exp(t)) \text{ if } t \leq 0\\

\end{cases}

$$

Finally, we will also need the Hessian for some second-order methods, which is given by

$$

\nabla_w ^2 \mathcal{L} = X^T D X + \lambda I

$$

where $I$ is the identity matrix and $D$ is a diagonal matrix given by $D_{ii} = \phi(y_i w^T X_i)(1 - \phi(y_i w^T X_i))$.

In Python, these function can be written as

def phi(t):

# logistic function, returns 1 / (1 + exp(-t))

idx = t > 0

out = np.empty(t.size, dtype=np.float)

out[idx] = 1. / (1 + np.exp(-t[idx]))

exp_t = np.exp(t[~idx])

out[~idx] = exp_t / (1. + exp_t)

return out

def loss(w, X, y, alpha):

# logistic loss function, returns Sum{-log(phi(t))}

z = X.dot(w)

yz = y * z

idx = yz > 0

out = np.zeros_like(yz)

out[idx] = np.log(1 + np.exp(-yz[idx]))

out[~idx] = (-yz[~idx] + np.log(1 + np.exp(yz[~idx])))

out = out.sum() + .5 * alpha * w.dot(w)

return out

def gradient(w, X, y, alpha):

# gradient of the logistic loss

z = X.dot(w)

z = phi(y * z)

z0 = (z - 1) * y

grad = X.T.dot(z0) + alpha * w

return grad

def hessian(s, w, X, y, alpha):

# hessian of the logistic loss

z = X.dot(w)

z = phi(y * z)

d = z * (1 - z)

wa = d * X.dot(s)

Hs = X.T.dot(wa)

out = Hs + alpha * s

return out

Benchmarks

I tried several methods to estimate this $\ell_2$-regularized logistic regression. There is

one first-order method (that is, it only makes use of the gradient and not of

the Hessian), Conjugate

Gradient

whereas all the others are Quasi-Newton methods. The method I tested are:

- CG = Conjugate Gradient as implemented in

scipy.optimize.fmin_cg

- TNC = Truncated Newton as implemented in

scipy.optimize.fmin_tnc

- BFGS = Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno method, as implemented in

scipy.optimize.fmin_bfgs.

- L-BFGS = Limited-memory BFGS as implemented in

scipy.optimize.fmin_l_bfgs_b. Contrary to the BFGS algorithm, which is written in Python, this one wraps a C implementation.

- Trust Region = Trust Region Newton method . This is the solver used by LIBLINEAR that I've wrapped to accept any Python function in the package pytron

To assure the most accurate results across implementations, all timings were

collected by callback functions that were called from the algorithm on each

iteration. Finally, I plot the maximum absolute value of the gradient (=the

infinity norm of the gradient) with respect to time.

The synthetic data used in the benchmarks was generated as described in and consists

primarily of the design matrix $X$ being Gaussian noise, the vector of

coefficients is drawn also from a Gaussian distribution and the explained

variable $y$ is generated as $y = \text{sign}(X w)$. We then perturb matrix

$X$ by adding Gaussian noise with covariance 0.8. The number of samples and features

was fixed to $10^4$ and $10^3$ respectively. The penalization parameter $\lambda$ was

fixed to 1.

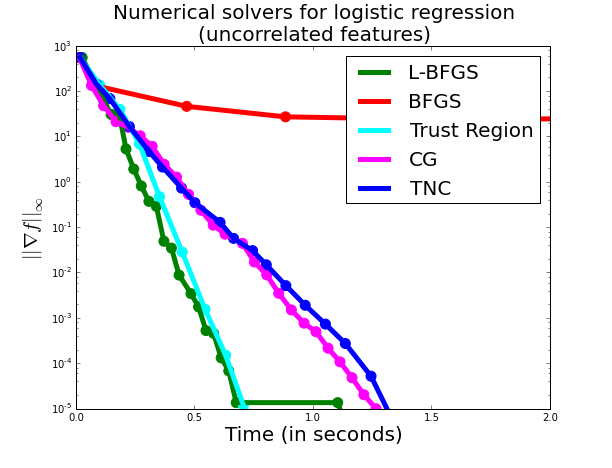

In this setting variables are typically uncorrelated and most solvers perform

decently:

Here, the Trust Region and L-BFGS solver perform almost equally good, with

Conjugate Gradient and Truncated Newton falling shortly behind. I was surprised

by the difference between BFGS and L-BFGS, I would have thought that when memory was not an issue both algorithms should perform similarly.

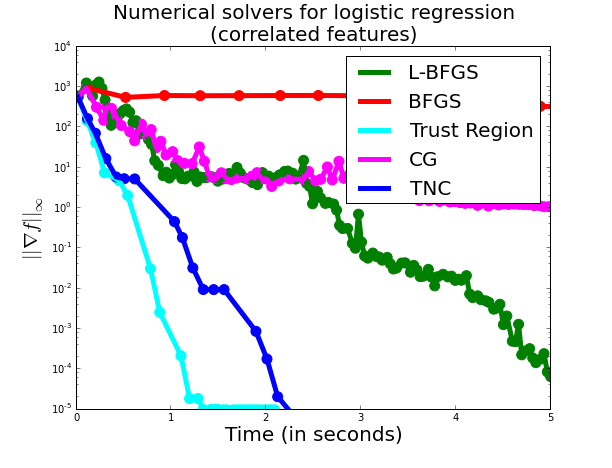

To make things more interesting, we now make the design to be slightly more

correlated. We do so by adding a constant term of 1 to the matrix $X$ and

adding also a column vector of ones this matrix to account for the intercept. These are the results:

Here, we already see that second-order methods dominate over first-order

methods (well, except for BFGS), with Trust Region clearly dominating the

picture but with TNC not far behind.

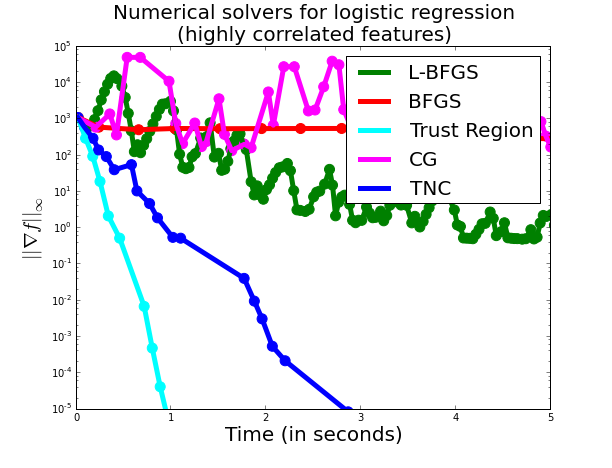

Finally, if we force the matrix to be even more correlated (we add 10. to the

design matrix $X$), then we have:

Here, the Trust-Region method has the same timing as before, but all other

methods have got substantially worse.The Trust Region

method, unlike the other methods is surprisingly robust to correlated designs.

To sum up, the Trust Region method performs extremely well for optimizing the

Logistic Regression model under different conditionings of the design matrix.

The LIBLINEAR software uses

this solver and thus has similar performance, with the sole exception that the

evaluation of the logistic function and its derivatives is done in C++ instead

of Python. In practice, however, due to the small number of iterations of this

solver I haven't seen any significant difference.

There are comments.